Becoming an Ocean Carer

Using ocean data to create a relationship of care between us humans and with the ocean.

BY Inna Zrajaeva

Inna wrote her master’s thesis in close collaboration with HUB Ocean and is HUB Ocean’s first graduate student. She holds an MA in Interaction Design from the Umeå Institute of Design in Sweden. She is originally from Uzbekistan and spent most of her life in Germany.

Standing on the beach in Malmö, a beautiful landscape is in view: the Öresund bridge connecting Malmö to Copenhagen, the historic Ribersborgs sauna– a popular spot in the city, and out in the distance, a large ship is passing by the harbor.

All that I see is from a single perspective—and of course, it is a human perspective. The bridge enables me to go to work each morning. A bathing house is a place for good coffee.

Öresund bridge | Source: unsplash

All these places and structures have a purpose for people, but I am not considering that those structures also influence the many living beings inside and around the waters. The bridge, for example, is also a habitat for a large community of blue mussels, the ship I see passing by will likely disturb the communication networks of Baltic cod.

The things we build create interactions with nonhumans as much as with humans and influence their lifepaths for better or worse.

Max Alonzo & Inna Zrajaeva

The ocean needs care

Unfortunately, these things usually end up being for the worse. Human influence on the ocean over the last decades has brought us to the terrible environmental situation we are in now.

To start to repair this relationship, we humans need to start seeing multispecies perspectives and find better ways of understanding how our culture (our creations and actions) influences other species.

For me, a relationship of care can be established by finding ways to coexist to achieve the best quality of life for humans and nonhumans.

Creating a relationship of care with the ocean can help us better understand it, not as a vast space to be used but as an assembly of actors with different needs and agencies.

Nonhuman perspectives and the digital twin

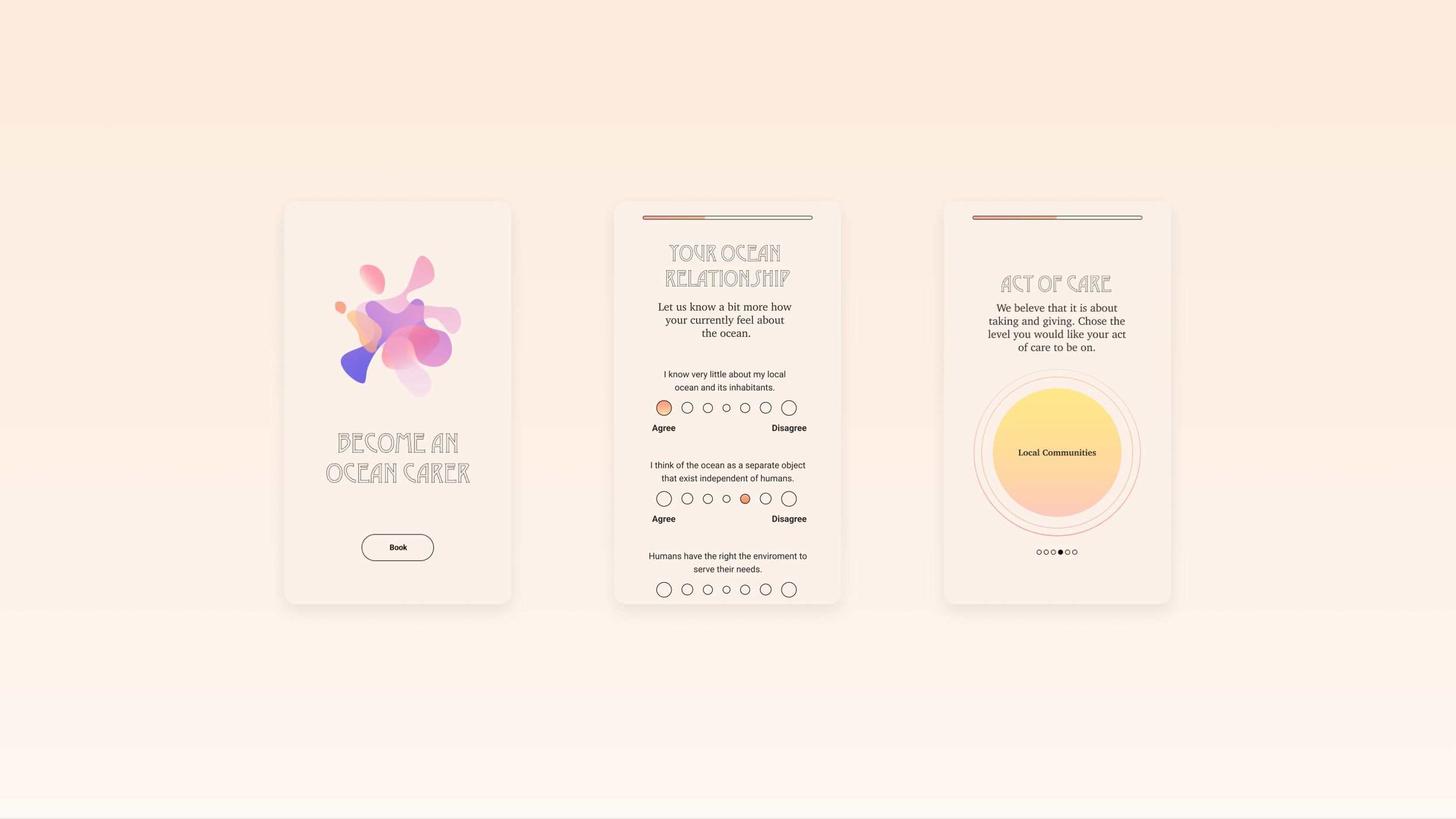

How could constructions from bridges to harbours to coastal neighbourhoods accommodate the needs of the population of green crab or bladderwrack? To take it further, how can digital structures be used to form relationships with aquatic life?

In my thesis, I looked at how we might apply multispecies perspectives to the structure of the digital twin of the ocean.

I argue that if we build the digital twin with the values of human domination rather than coexistence, we will reproduce the ecological problems we face today.

Becoming an Ocean Carer

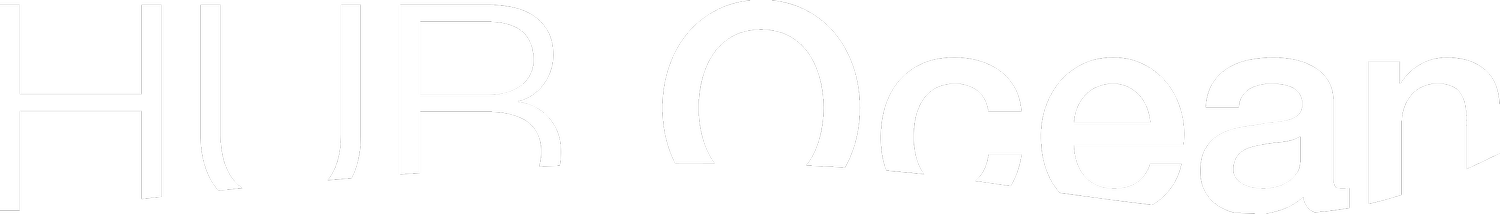

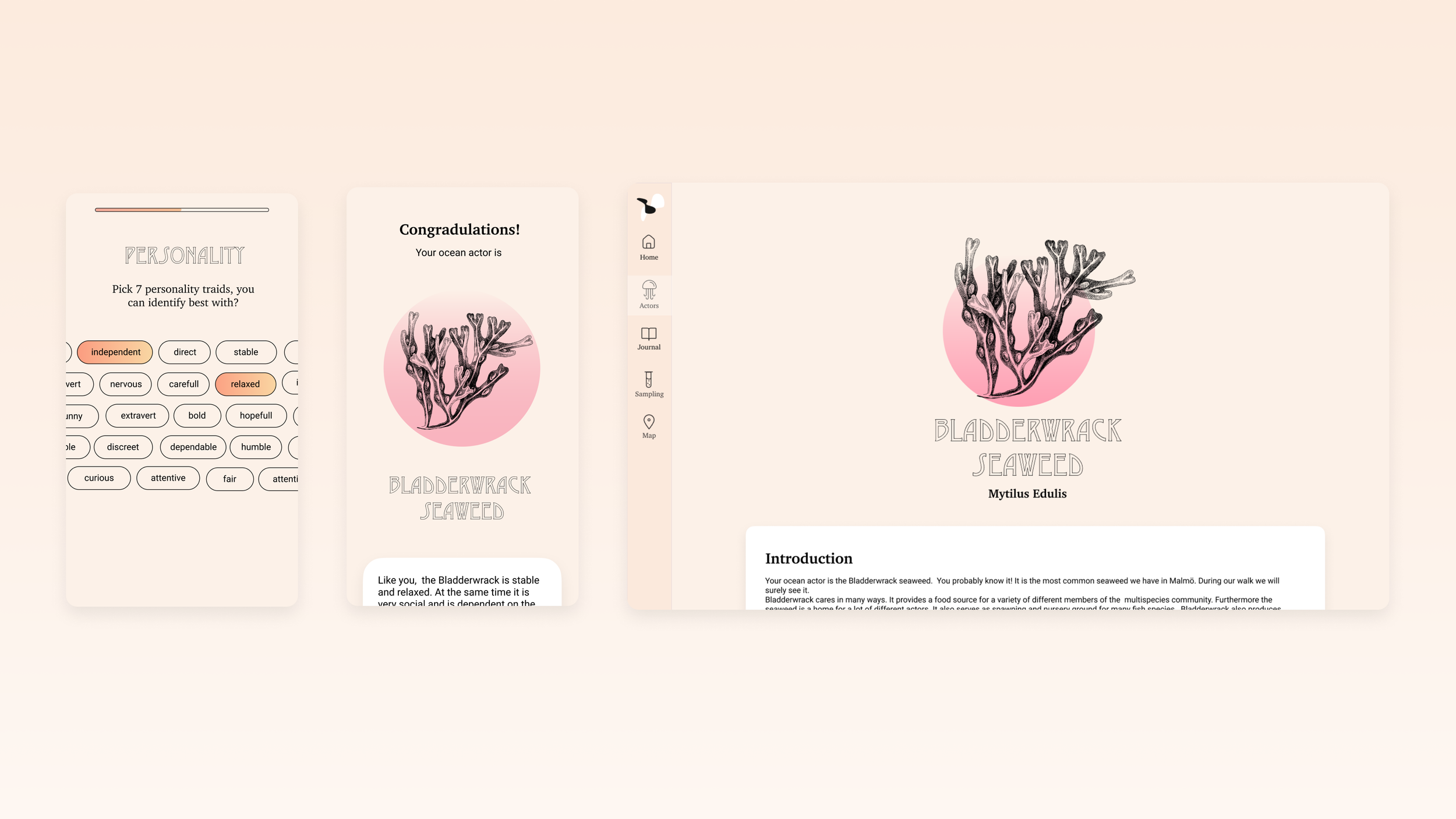

My research findings offer an alternative approach through an experience modelled for ocean observatories called “Becoming an Ocean Carer.” Working with the Naturturum Öresund, a marine pedagogy centre in Malmö, I tested the experience with participants.

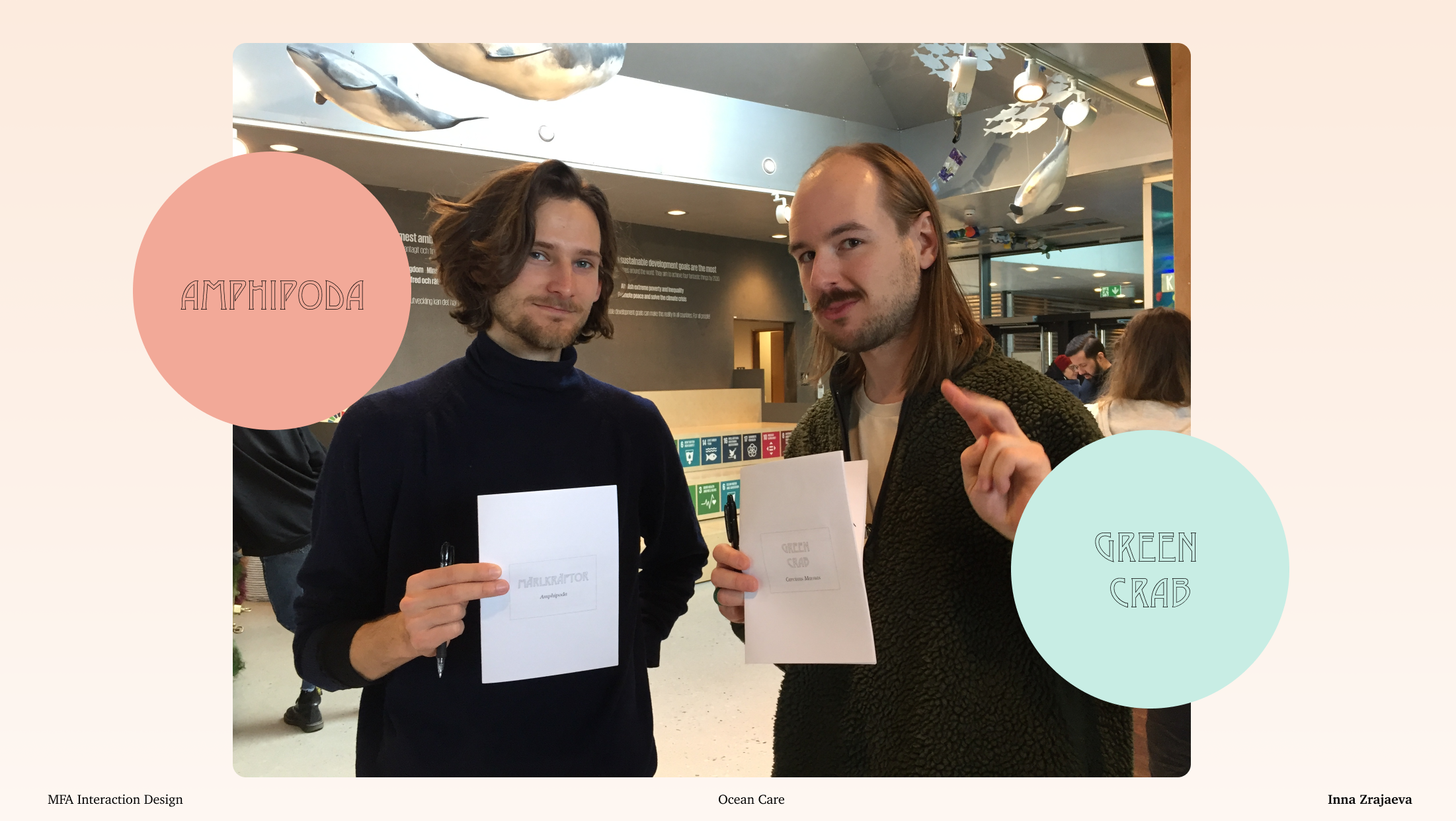

The experience starts with a test the visitors take that matches them with an ocean actor, about which they are invited to learn more. The participants are then teamed up in small ecosystem groups to work together, allowing them to think beyond the single-actor perspective. This enables the participants to learn how their actors are connected and reflect on interdependencies and relations between actors and human influences.

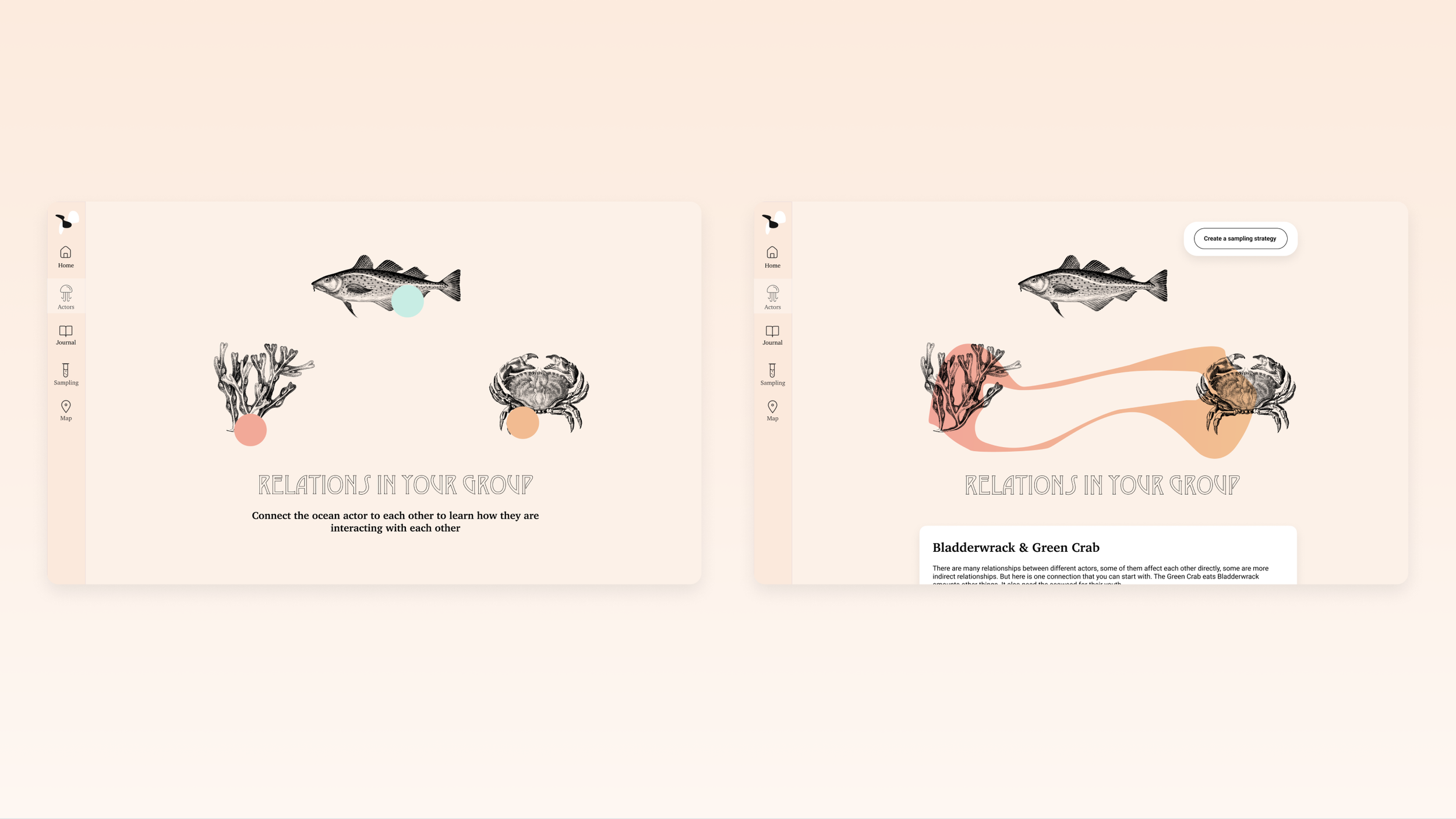

With the perspective of their actors and ecosystem in mind, participants plan a sampling strategy deciding where they want to take samples and reflecting on how human structures might interact with their nonhuman actors.

The participants go outside and take samples at the spots they selected. After this, the participants are invited to tell the story of their journey, sowing a deeper bond to the beings behind the ocean data they have collected.

As a final activity, the participants are invited to come up with ideas for how they can change the way they affect their ocean community.

Quick understanding of threats to the ecosystem

Ecosystem

During the test, participants quickly identified with their assigned ocean actors even if they did not know about them. Furthermore, they learned about their environment from an ecosystem perspective.

For example, they learned about Lynette Holm: a land extension project in Copenhagen that might pose a threat to the ecosystem due to the pollution from the construction and the extraction and displacement of sand and sediment in the Öresund.

Participants also quickly understood ocean data’s potential while working on their sampling strategy. An essential part of this test was that they had to reflect on how they could help the ocean actors they were representing.

Ways to include the perspective of ocean inhabitants

Once it is embedded in a system, exploitation is very difficult to root out, as we are now painfully learning from feminist and decolonial movements. To avoid the same challenges and needless exploitation of the sea, we might build the oceans’ digital twin on these new values of care.

With this in mind, my thesis and the Ocean Carer experience take the first steps by asking: how might we find ways to include the perspective of ocean inhabitants to create a sensitive and caring relationship with the ocean?

The experience is not designed to humanise other species. After all, we will never know what it is to be a green crab or baltic cod. But instead, it invites people to become more aware and sensitive to the nonhumans with whom we share our environment. It is a process of naturalising humans.